Thursday, March 30, 2006

The Lesbian Novel and Me

Just up the road is Jeanette Winterson. She has a flat above a shop, but does not, presumably, count herself among the common people as she owns the shop, the flat, the entire crooked building and paid for it all in cash, by (and from) her own account. She doesn't seem to get out much. I wonder about her, if she spends the daylight hours hunched over a William and Mary bureau scribbling in tiny copperplate, if she's shy, or nocturnalised, if after years of front and forthrightness she's rethought herself as an inner city recluse. It's a strange, though gorgeous spot to choose for the pursuit of a quiet life. When I have seen her, climbing the stairs with a glass vase of lilies, or looking out of her crooked house windows at a commotion in the street, I've been jolted somewhat. Writers are people that we encounter through their work, and it is unnerving to see them engaged in private pursuits, interrupted, distracted. And Winterson belongs to, or rather comes from an entirely other England than me. Northern, God-fearing, gay. I am glad that she has been around, being Jeanette Winterson, for the last fifteen years, even though I struggle with her fiction. There is an iconic quality about her, that goes beyond her hair, or her nose. I remember that the tendons on her forearms would stick out when she squeezed some emphasis into a fist on late night discussion programs. She always seemed convinced, and as a result was often convincing, in her arguments. Now she has a shop, albeit a very special one. She is Roger of the Raj.

Friday, March 17, 2006

Better Living Through Chemistry

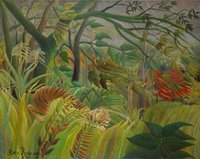

There is an Indian folk tale about the tiger and the tiger's child. It's a parable about domestication. The tiger is distracted by the tiger's child and lets his fire burn out. He sends his child to the man village to bring back fire so that he can cook their food; he cannot go himself as the people in the man village are afraid of him. The tiger's child reaches the man village where he is admired and spoiled by the people. He falls asleep in front of a fire and turns into a cat, forgetting why he came to the village. Since that time the tiger has always eaten his food raw. And the cat has always lived among people.

There is an Indian folk tale about the tiger and the tiger's child. It's a parable about domestication. The tiger is distracted by the tiger's child and lets his fire burn out. He sends his child to the man village to bring back fire so that he can cook their food; he cannot go himself as the people in the man village are afraid of him. The tiger's child reaches the man village where he is admired and spoiled by the people. He falls asleep in front of a fire and turns into a cat, forgetting why he came to the village. Since that time the tiger has always eaten his food raw. And the cat has always lived among people.I mention this only because my wife and I were in the kitchen earlier and while she danced around in her nightwear, a bottle of wine to the good, I admired the effect that the descaler I was using was having on the grimly geological deposits around the base of the mixer tap.

I was once a tiger. Now I am Bagpuss. Emily loves me. If I could just find out where she lives I'd be set.

Monday, March 13, 2006

Wonderboy and Waxgirl

It has been seven days since my last confession. I have, of course, sinned in thought, word and deed without interruption since then. But not in such a way as to make the world a worse place, so I'm giving myself a mulligan. The swearing and the lusting are par for the course (end of metaphor) but I have been surprised by the gluttony. If it is gluttony. I am really hungry all the time, like Roy Hobbs in "The Natural".

It has been seven days since my last confession. I have, of course, sinned in thought, word and deed without interruption since then. But not in such a way as to make the world a worse place, so I'm giving myself a mulligan. The swearing and the lusting are par for the course (end of metaphor) but I have been surprised by the gluttony. If it is gluttony. I am really hungry all the time, like Roy Hobbs in "The Natural".What am I so hungry for? Will this hunger ever be satisfied? Will I have to sell my soul at any point?

The ENT consultant discharged my daughter this morning. Her hearing is normal, although he did remove an impressive clod of wax from her left ear before she took her test. It's a relief to know that she has simply been ignoring us, on and off, for the last five years. When I was young and deaf among the apple boughs audiologists were crabby, disapproving women of a certain age. Nowadays, based on recent visits to the soundproof booth, they are young, exotic, friendly and hot. I am considering feigning some flutter and wow in order to get tested.

The consultant was "a funny man" according to my daughter. Which is funny ha-ha. He was fantastic with her and reminded me of a chap from school, Mike, who I always liked, but never got to know. His father was a bit like mine, but with money. Mike had a lovely girlfriend who wouldn't let him sleep with her but he claimed never to masturbate. I, for some reason, chose to believe this; I think I was the only one who did.

Monday, March 06, 2006

Death To Police Pigs

You arrive in the grey, tatty bus station, on a cold afternoon. You are seventeen years old, you have just spent twenty-four hours on a coach as old as you are and you are lost in Central Europe. Your sister, Miranda, has failed to meet you. She has gone to Dresden for the weekend although you do not know this yet. You wait around for half an hour, your body temperature steadily declining, hoping that she'll turn up. When she doesn't you walk up the most civilised-looking street and change some money at a casino. You 'phone home. Your father, as distracted as you expect he'll be, answers.

"What? Hello."

"Daddy, it's Dickie," you say. That's your name.

"Hello sunshine, how's Prague?"

"It's terribly cold," you tell him. "And Miranda's not here."

"Ah yes," you can sense his attention wandering, "I think we know about that. I'll get your mother."

You hear a series of noises apparently unrelated to the retrieval of your mother, punctuated by the familiar barking sound that your father makes when he's not getting his own way.

"Dickie, it's Mum. Miranda's gone to Germany with her boyfriend, I'm afraid."

" --- " You still don't swear in front of your mother.

"She says you’re to go the English faculty at the University and ask for Josef."

You thank your mother, consult your guide book, and head off as instructed. On route you buy from a roadside vendor a beer and a wurst both of which are remarkably good and inexpensive. This cheers you somewhat. The English faculty is closed when you get there, however, and you resign yourself to a premature death, slumped in a Czech doorway. This the only fate that awaits you. You have another beer, and another.

Hours later you find yourself huddled for warmth between two amply proportioned Australian girls on the concourse of the main station. They are trying to persuade you to follow them to Munich. They leave on a 5.30 train, before it gets light. You wander slowly back towards the University. You are ineffably tired. There is a warm waiting room outside the faculty office and a sour-faced security guard defies your expectations by letting you wait there. You fall asleep. No-one disturbs you.

"Dickie? Are you Dickie?" A frog-faced man with excitable hair is shaking you awake. A large camera swings from his neck. "I am Josef, I expected you yesterday."

He takes your rucksack and leads you outside. "We'll get coffee," he says. "And then we'll find you somewhere to stay."

"Okay." The idea of finding a bed is extraordinarily appealing, and you are content to follow this man, this stranger, anywhere, if he can secure you somewhere comfortable to sleep. You emerge into a Prague morning that smells of spring. The overcast skies have been replaced by blue brilliance and a fierce, low sun.

You have some indifferent coffee in an underground restaurant and Josef argues about the bill. Eventually the proprietor waves him away and you leave without paying.

"Now, accommodation!" Josef pulls you onto a tram and within minutes you are back where you started, at the bus station.

In a backstreet office the two of you sit down opposite a long-legged woman with a severe haircut. She sounds, you remark to yourself, like the villain's plaything in a James Bond film. There's something transfixing about her. Josef stares at her with accustomed blatancy.

"I have a place in the Jewish Quarter, but it's expensive."

"How much?"

"Sixty deutschmarks."

"I can't afford that, I'm sorry." The long-legged woman looks a little perturbed and Josef kicks you in the back of the ankle.

"That price is for the week?" he asks. She nods and you feel foolish, and a little cheap.

Your new home has twelve foot ceilings, a grand piano, pictures of Masaryk, creaking bookcases, chandeliers of the finest Bohemian crystal, views outward over the Vltava and inwards over a broad atrium strung with washing lines like streamers. You experience a strange sensation, when Josef leaves you alone here for the first time, that the owners have only just left and will shortly return. You, Goldilocks, find the largest bed you can and fall asleep on it.

For the second time today you are woken by your diminutive guide. He is knocking on the door of the apartment and shouting, in different voices:-

"Dickie, Dickie, DICKIE!"

You struggle into an upright position and realise that you have been wearing the same clothes for more than two days. You let Josef in.

"Come, come," he says. "There's to be a demonstration."

"About what? I thought everything was okay now. I thought you had your revolution."

"They're protesting against the Police."

"Why?" you ask.

"The cops are like a secret society. Lots of them who had senior jobs under the Communists are still working there."

You make your way towards the New Town. Protestors are gathering at the bottom of a broad thoroughfare. "Wenceslas Square," Josef tells you. The crowd swells quickly, but everything still seems relatively good-humoured. A brace of jittery policemen, who seem to be about your age, study the crowd palely. They are armed, you notice. The crowd, five or six thousand, at best guess, begin to move. A banner is unfurled up front, it reads something like - DEATH TO POLICE PIGS - according to Josef. It occurs to you that such a message isn't really in the spirit of the Velvet Revolution. You turn towards Josef to make this observation but he is off, snapping away. The crowd has begun to chant and punch the air. He returns a few moments later, still taking photographs. You mention the banner and he laughs.

"Of course a lot of these people aren't Czech," he explains. They're international anarchists here to start trouble." As if to illustrate this assertion one protestor, his face half-covered by a black neckerchief, tries to snatch Josef's camera. "Polizei?" he demands. You step between them, walking backwards, as Josef spins the camera around to his back. He waves his press credentials over your shoulder into the German's face. "Photographer," he shouts. "Czech photographer."

The march moves forward. Depressingly, you realise that once again you are heading back towards the bus station. But the crowd are getting angrier now, and the whole thing, you admit to yourself, is exciting. People join the crowd from side streets. Josef is struggling to contain himself. "This is going to be good," he says.

The police station is in one of the older buildings in this part of town. When the protestors get there they balloon outwards around the main steps and raise the volume of their chanting. You and Josef climb the wall beside the steps so that you're looking down slightly at the crowd.

A coin is thrown by someone, you can't see who. The crowd exhales. Then more coins, you can't see them hitting the windows but you can hear them clacking against the glass before they fall to the pavement. People are looking for stones to throw but there are none. The coin throwing stops and Josef and you go down into the crowd. A man in a peaked cap with epaulettes on his uniform has appeared in a second floor window. He is appealing for calm but sounds angry himself. The crowd, quietened initially begin to shout again.

"Golf balls," says Josef. He points at the entrance to the department store on the other side of the small plaza, he stuffs some notes into your pocket, deutschmarks. "Get as many as you can." His amphibian face is infused with an irresistible glee. You nudge your way through the mob. Inside the store everything continues in serene disregard to the events taking place across the square. Muzak plays. Scents are sampled. You walk briskly towards the sporting goods department, laughing. You buy around two hundred golf balls, emptying out the deutschmarks. The assistant thanks you, in English. You run back downstairs and onto the street. Josef finds you before you even see him. "Great," he says. "Now give them to the Germans." You don't move. "Trust me," he says, and you decide to do so. The same German you saw before seems to be in charge and he thanks you, again in English, for the ammunition.

The balls go up, harder, flatter. Again they're aiming at the windows, and this time the windows are smashing. Many of the balls miss their target, however, and ping back at unpredictable angles from the aged masonry onto a cowering crowd. By now you’re back on the steps, watching this happen. Josef is cackling like a madwoman and it is now that you appreciate the genius of his idea. From where you are it looks as though the police are attacking the crowd. Golf balls are retrieved and hurled again. The crowd grow still angrier. Soon the police really are throwing the balls back at the mob. Eventually someone fires a shot in the air. The crowd flinches, retreats a step, and then roars again. Josef has run out of film and he grabs your shoulder and begins to direct you away from the steps. "In case things turn nasty," he explains.

Later the two of you are drinking in a small bar in the old town. You are falling in love with the waitress who is only a little older than you, and who keeps ruffling your hair when she goes past.

"You can teach me good English" she says, bringing you gin and tonics. You laugh and she looks offended, just momentarily.

"What did you do today, little boy?"

"Another drink and I will tell you, I promise." Josef laughs. But he is shaking his head.

"What? Hello."

"Daddy, it's Dickie," you say. That's your name.

"Hello sunshine, how's Prague?"

"It's terribly cold," you tell him. "And Miranda's not here."

"Ah yes," you can sense his attention wandering, "I think we know about that. I'll get your mother."

You hear a series of noises apparently unrelated to the retrieval of your mother, punctuated by the familiar barking sound that your father makes when he's not getting his own way.

"Dickie, it's Mum. Miranda's gone to Germany with her boyfriend, I'm afraid."

" --- " You still don't swear in front of your mother.

"She says you’re to go the English faculty at the University and ask for Josef."

You thank your mother, consult your guide book, and head off as instructed. On route you buy from a roadside vendor a beer and a wurst both of which are remarkably good and inexpensive. This cheers you somewhat. The English faculty is closed when you get there, however, and you resign yourself to a premature death, slumped in a Czech doorway. This the only fate that awaits you. You have another beer, and another.

Hours later you find yourself huddled for warmth between two amply proportioned Australian girls on the concourse of the main station. They are trying to persuade you to follow them to Munich. They leave on a 5.30 train, before it gets light. You wander slowly back towards the University. You are ineffably tired. There is a warm waiting room outside the faculty office and a sour-faced security guard defies your expectations by letting you wait there. You fall asleep. No-one disturbs you.

"Dickie? Are you Dickie?" A frog-faced man with excitable hair is shaking you awake. A large camera swings from his neck. "I am Josef, I expected you yesterday."

He takes your rucksack and leads you outside. "We'll get coffee," he says. "And then we'll find you somewhere to stay."

"Okay." The idea of finding a bed is extraordinarily appealing, and you are content to follow this man, this stranger, anywhere, if he can secure you somewhere comfortable to sleep. You emerge into a Prague morning that smells of spring. The overcast skies have been replaced by blue brilliance and a fierce, low sun.

You have some indifferent coffee in an underground restaurant and Josef argues about the bill. Eventually the proprietor waves him away and you leave without paying.

"Now, accommodation!" Josef pulls you onto a tram and within minutes you are back where you started, at the bus station.

In a backstreet office the two of you sit down opposite a long-legged woman with a severe haircut. She sounds, you remark to yourself, like the villain's plaything in a James Bond film. There's something transfixing about her. Josef stares at her with accustomed blatancy.

"I have a place in the Jewish Quarter, but it's expensive."

"How much?"

"Sixty deutschmarks."

"I can't afford that, I'm sorry." The long-legged woman looks a little perturbed and Josef kicks you in the back of the ankle.

"That price is for the week?" he asks. She nods and you feel foolish, and a little cheap.

Your new home has twelve foot ceilings, a grand piano, pictures of Masaryk, creaking bookcases, chandeliers of the finest Bohemian crystal, views outward over the Vltava and inwards over a broad atrium strung with washing lines like streamers. You experience a strange sensation, when Josef leaves you alone here for the first time, that the owners have only just left and will shortly return. You, Goldilocks, find the largest bed you can and fall asleep on it.

For the second time today you are woken by your diminutive guide. He is knocking on the door of the apartment and shouting, in different voices:-

"Dickie, Dickie, DICKIE!"

You struggle into an upright position and realise that you have been wearing the same clothes for more than two days. You let Josef in.

"Come, come," he says. "There's to be a demonstration."

"About what? I thought everything was okay now. I thought you had your revolution."

"They're protesting against the Police."

"Why?" you ask.

"The cops are like a secret society. Lots of them who had senior jobs under the Communists are still working there."

You make your way towards the New Town. Protestors are gathering at the bottom of a broad thoroughfare. "Wenceslas Square," Josef tells you. The crowd swells quickly, but everything still seems relatively good-humoured. A brace of jittery policemen, who seem to be about your age, study the crowd palely. They are armed, you notice. The crowd, five or six thousand, at best guess, begin to move. A banner is unfurled up front, it reads something like - DEATH TO POLICE PIGS - according to Josef. It occurs to you that such a message isn't really in the spirit of the Velvet Revolution. You turn towards Josef to make this observation but he is off, snapping away. The crowd has begun to chant and punch the air. He returns a few moments later, still taking photographs. You mention the banner and he laughs.

"Of course a lot of these people aren't Czech," he explains. They're international anarchists here to start trouble." As if to illustrate this assertion one protestor, his face half-covered by a black neckerchief, tries to snatch Josef's camera. "Polizei?" he demands. You step between them, walking backwards, as Josef spins the camera around to his back. He waves his press credentials over your shoulder into the German's face. "Photographer," he shouts. "Czech photographer."

The march moves forward. Depressingly, you realise that once again you are heading back towards the bus station. But the crowd are getting angrier now, and the whole thing, you admit to yourself, is exciting. People join the crowd from side streets. Josef is struggling to contain himself. "This is going to be good," he says.

The police station is in one of the older buildings in this part of town. When the protestors get there they balloon outwards around the main steps and raise the volume of their chanting. You and Josef climb the wall beside the steps so that you're looking down slightly at the crowd.

A coin is thrown by someone, you can't see who. The crowd exhales. Then more coins, you can't see them hitting the windows but you can hear them clacking against the glass before they fall to the pavement. People are looking for stones to throw but there are none. The coin throwing stops and Josef and you go down into the crowd. A man in a peaked cap with epaulettes on his uniform has appeared in a second floor window. He is appealing for calm but sounds angry himself. The crowd, quietened initially begin to shout again.

"Golf balls," says Josef. He points at the entrance to the department store on the other side of the small plaza, he stuffs some notes into your pocket, deutschmarks. "Get as many as you can." His amphibian face is infused with an irresistible glee. You nudge your way through the mob. Inside the store everything continues in serene disregard to the events taking place across the square. Muzak plays. Scents are sampled. You walk briskly towards the sporting goods department, laughing. You buy around two hundred golf balls, emptying out the deutschmarks. The assistant thanks you, in English. You run back downstairs and onto the street. Josef finds you before you even see him. "Great," he says. "Now give them to the Germans." You don't move. "Trust me," he says, and you decide to do so. The same German you saw before seems to be in charge and he thanks you, again in English, for the ammunition.

The balls go up, harder, flatter. Again they're aiming at the windows, and this time the windows are smashing. Many of the balls miss their target, however, and ping back at unpredictable angles from the aged masonry onto a cowering crowd. By now you’re back on the steps, watching this happen. Josef is cackling like a madwoman and it is now that you appreciate the genius of his idea. From where you are it looks as though the police are attacking the crowd. Golf balls are retrieved and hurled again. The crowd grow still angrier. Soon the police really are throwing the balls back at the mob. Eventually someone fires a shot in the air. The crowd flinches, retreats a step, and then roars again. Josef has run out of film and he grabs your shoulder and begins to direct you away from the steps. "In case things turn nasty," he explains.

Later the two of you are drinking in a small bar in the old town. You are falling in love with the waitress who is only a little older than you, and who keeps ruffling your hair when she goes past.

"You can teach me good English" she says, bringing you gin and tonics. You laugh and she looks offended, just momentarily.

"What did you do today, little boy?"

"Another drink and I will tell you, I promise." Josef laughs. But he is shaking his head.

Sunday, March 05, 2006

The Sea, The Sea

We found time to get to Southend yesterday, and the winter sunshine was enough to temper the essentially desolate feeling that you get in a seaside town, out of season. My daughter had fun, and my wife and I realised that we could never, ever, live somewhere like that, somewhere so very white and otherwise socially homogenous, somewhere opposite, in fact, to where we live now. The reasons behind this conviction are probably different for the two of us. I was brought up in a medium-sized town that was almost exclusively white and middle-class, and if the experience hasn't scarred me exactly, it must have hampered the development of my sense of community and of personal and social responsibility. My wife was raised in the Babel of the East End, however, and has never left it, and would miss it terribly if she did. We had an expected house-guest the other evening, a friend of my wife's who had missed her train. When quizzed by a third party about her stay in Stratford she was broadly disparaging and pointed out that, after all, she was from the country. To us, the country is somewhere you might want to visit, but not somewhere you might conceivably want to live. Southend, by no means uniquely, has neither the obscure charm of the country, nor the diverse delights of the city. It has the sea, though, which is what took us there, and not against our wishes.

We found time to get to Southend yesterday, and the winter sunshine was enough to temper the essentially desolate feeling that you get in a seaside town, out of season. My daughter had fun, and my wife and I realised that we could never, ever, live somewhere like that, somewhere so very white and otherwise socially homogenous, somewhere opposite, in fact, to where we live now. The reasons behind this conviction are probably different for the two of us. I was brought up in a medium-sized town that was almost exclusively white and middle-class, and if the experience hasn't scarred me exactly, it must have hampered the development of my sense of community and of personal and social responsibility. My wife was raised in the Babel of the East End, however, and has never left it, and would miss it terribly if she did. We had an expected house-guest the other evening, a friend of my wife's who had missed her train. When quizzed by a third party about her stay in Stratford she was broadly disparaging and pointed out that, after all, she was from the country. To us, the country is somewhere you might want to visit, but not somewhere you might conceivably want to live. Southend, by no means uniquely, has neither the obscure charm of the country, nor the diverse delights of the city. It has the sea, though, which is what took us there, and not against our wishes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)